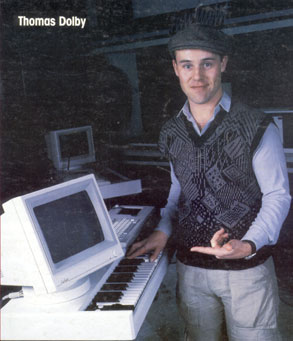

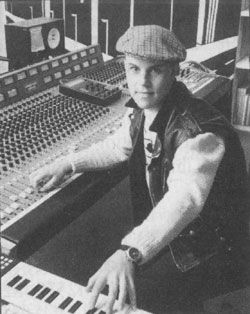

Interview with Thomas Dolby by Craig Anderton

from Electronic Musician June 1986

Thomas Dolby's Golden Age of Wireless album applied high technology to dance-floor sensibility, and produced a monster hit("She Blinded Me with Science") in the process. His follow-up, The Flat Earth, showed a willingness to branch out in different directions and explore more than just the safe synth-pop turf.

Recently, Dolby has done the music for the Lucas Film Howard the Duck, collaborated with George Clinton, produced Joni Mitchell's latest album, and has generally kept active in a number of fields. He has the kind of schedule that makes him a tough person to pin down, but we finally caught up with him electronically--36,000 feet over Greenland.

EM: You describe yourself not as a musician, composer, or video specialist but rather as an "inventor." Do you, as do man of our readers, find terms like "keyboard player" or "musician" too limiting?

TD: Labeling is something you tend to tolerate rather than encourage. It's what journalists and A&R people and radio programmers--all my favorite people in the world!-- do in order to neatly categorize music and file it away into pigeonholes. I've always tried to cut through those labels. Not because I wanted to go down in history as an "original" or an "innovator," but because my creative adrenalin only starts flowing when I sense I'm stretching myself. So I ended up calling myself "inventor." That's also down on my British passport as my profession.

EM: Are your inventions more conceptual or physical, and in what environment do you do your inventing?

TD: I've recently completed my studio in London, the ThinkTank. I love it--it's the perfect playpen for an artistic delinquent like myself. It was formerly a painter's studio and is very light and airy, with wood beams and huge windows and its own cast iron staircase and front door. I chose to use the largest part of the space for the control room, in order to accommodate my video equipment (a small Sony 3/4-inch editing system, Fairlight CVI, and a large screen Barco projector over the mixing board) along with a large battery of electronic percussion (E-mu SP12, Linn 9000, and assorted Simmons and PPG modules) and my new Fairlight Series III and Emulator II. I've never sold a keyboard, even my first two-a Micromoog and a Roland JP4 with which I recorded everything in "She Blinded My With Science." Usually I can find the texture I'm looking for through a combination of the different components. But what's really great about the studio is that it's not an oppressive working environment, because it's very spacious and free of studio managers waving enormous bills in my face! And I don't think my record company even knows where it is.

Before the equipment went in there, I consulted an acoustician who said I would have to flatten the ceiling, raise the floor, narrow down the windows and drape the walls to achieve a flat sound. I'm really glad now that I didn't take his advice, because it's unquestionably the nicest and most sonically accurate recording studio I know. He also told me that the kitchen off to the side was unsuitable for recording live sound - also wrong. So much of the theories surrounding studio sound are pure hokum; it's really a question of your approach. Which brings me around to your question - my "inventions" are really no more than imaginative explorations of the machines I already own, and new uses for them.

EM: It has been a long time since you last solo album, The Flat Earth. Since then you have been involved in a number of collaborative projects. Why have you gone in this direction?

TD: I'm enjoying collaborating more and more - after a long spell of working very much on my own, with something to prove to the world I suppose, I've gotten a lot more gregarious as an artist, probably less egotistical. I', always eager to impress whoever it is I'm working with, and that has the effect of bringing out a side of me that often I hadn't seen before. George Clinton got me harking back to a lot of my earliest influences, which unlike a lot of British musicians were not so much the Beatles and Stones as the American R&B I found late at night on European U.S. Armed forces Radio stations. And that man in funny! I think he watched too much TV as a foetus. Ryuichi Sakamoto was amazing to work with; we has a hard time understanding each other on a language level, but no trouble communicating through our music and visual imagery. To work with Joni Mitchell was a teenage fantasy of mine - she's a sublime artist, set apart from almost anyone. I like the Dog Eat Dog album, but making it was like a series of dental appointments. Not my most treasured memory. What's important though is the end result, which stands up on its own. the Prefab Sprout album was probably my favorite production job: I really admire Paddy MacAlloon as a writer and singer, and I tried to step outside myself and do everything possible to complement his wonderful music with my experience as an arranger and the technology of the studio.

EM: How does a composition start for you?

TD: My songs usually start with a title often a title that is memorable and suggestive enough that the music and the rest of the words follow on..."Airwaves," "One of our Submarines," "Mulu the Rain Forest," "Screen Kiss." Then there follows this strange exploration of the mystery that the title conjures up. For example on "Mulu" I started with a rhythm made up of tsikada insects and trees falling down in a jungle, then blew over the top of a milk bottle to make a Fairlight pan pipe sound and found a melody. As I hummed along, words started to form which often tied in with the subject--"dreamtime/faultline,""warning/morning dew/ Mulu," etc. It's all about atmosphere, really. I just try to climb inside my subject and squeeze out every drop of detail that adds to it, until one night I can sit back and listen and know it's all there, and then I mix it...which I suppose is not much more than the art of making all those impressions onto a piece of half-inch tape.

EM: What is a typical Thomas Dolby recording session like?

TD: I've always avoided using multi-track where possible. In the old days that was a lot more difficult to do--most sequencers would only run from the start of a song, which made mixing a nightmare, because the way I like to mix is to get a section at a time right and then find ways of blending the sections together. Nowadays with the use of SMPTE, most new machines will play from wherever you start the tape. So only vocals and acoustic instruments really have to be on multi-track, and will pretty soon be recorded digitally into powerful sampling devices in full anyway. Actually, I wouldn't give multi-track analog tape recorders more than a couple of years before they're junk, like the old Mellotrons. Charles Darwin should be alive today, he'd have a lot to say about recording studios, and rock 'n roll in general for that matter.

EM: Could you describe your favorite musical equipment?

TD: Anything made by PPG. I discovered PPG in about 1981; it sounded very clean and bell-like--long before Yamaha DX7 of course--and looked like it had been designed by a Frankfurt University professor, which was more of less the case. It also appealed to me because I sensed that clean, glassy digital sounds would one day replace the grittier analog synth timbres. I remember when Kraftwerk, whom I had always adored, came out with their Computerworld album after a long wait; I was disappointed. Compared to Trans Europe Express and Man Machine, perhaps the definitive electronic dance records, this seemed wimpy and insidious. After a couple of plays, it resided on my file-in-forget shelf for a good 18 months. Then one day I listened to it again, and it sounded utterly brilliant. The thought hit me that tastes develop in parallel with, but slightly behind, advances and innovations in musical technology. Like guitar sounds--if, in 1971, you'd heard a sample of the clean sustained chordal sounds later used by Andy Summers, you'd have probably considered it wimpy and insidious too. It was the difference between a Les Paul through a Marshall and an echoplexed, Fender modified-by-AMS-signal-processor-through-Roland Chorus Echo. but nowadays Hendrix records and Cream records sound clumsy and distorted.

Actually, the first PPG I bought was a giant Wave computer the size of a deepfreeze that was the prototype for the Wave. It went wrong constantly, no one in England knew how they worked, and their designers were always too busy soldering to by of any assistance. But it was the one machine that I never learned inside out, because it is endlessly variable and unpredictable, and that meant that I could always count on it to give me a new sound if I got stuck. Like the bass sound on "Windpower," which had a built-in swing rhythm to it, and fitted so will into the feel of the song that I've performed the song live, on occasions, with only that bass sound and my voice.

Elsewhere, my favorite sequencer is the Fairlight Page R, and my favorite echo machines are the Roland 555 Chorus Echo and the Yamaha REV-1. The funkiest drum machine ever is the E-mu SP12.

EM: Are you concerned that the price tag for getting involved with musical electronics is getting prohibitively high for those who, ten years ago, would have started garage bands?

TD: No, because overall music is now more accessible rather than less. It wasn't easy purring garage bands together either, especially with no money, but it had to happen, because people put up with whatever hardships faced them if they really wanted to get themselves heard.

EM: You have received as much attention for your videos as for your music. How active are you in the storyboarding, production, direction, etc.?

TD: That really varies according to how much time I have and how complicated my performing role is. "Science.""Dissidents" and "I scare Myself" took around seven to eight weeks each as I conceived, wrote, directed and edited them myself. "Hyperactive" and "May the Cube be With You" were conceived by me but directed by others.

A lot of people complain about videos, and you've heard all the arguments. I feel that if the world takes a particular turn, there's not a lot of point in bitching about it, you have to evolve with it as an artist or hop off. As long as releasing singles and making videos entertained and challenged me, I stuck with it; but one day I just thought, there's got to be a more dangerous way to make a living, and I looked around and found it, for a while at least, in films.

|

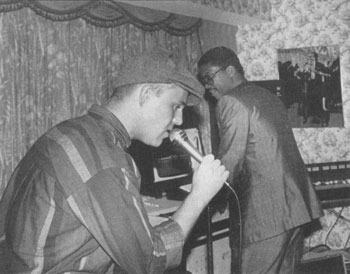

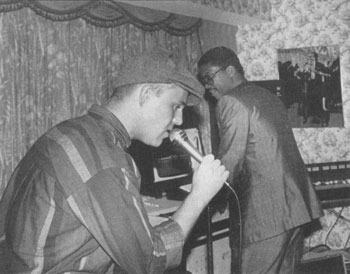

| Dolby and Herbie Hancock jam at Fairlight's party at a recent NAB convention in Las Vegas. Dolby is improvising with a Voicetracker. |

EM: Describe your recent project, working with LucasFilm on Howard the Duck...

TD: In the fall of 1985, I was approached by Quicy Jones' company Cinemascore to score a movie entitled Fever Pitch, directed by Richard Brooks and starring Ryan O'Neal. I was very pleased to get that opportunity and accepted. Unfortunately, the film turned out to be a damp squid, but it was worthwhile for me because it showed me what I could and couldn't do within the film medium, and introduced me into the very tight-knit Hollywood music clique. Very soon after, I was asked to contribute one song to a Lucas movie called Howard the Duck, based on a '70s adult comic. I read the script and was frankly much more interested in doing the score--I've always enjoyed cartoon music and the concept of a large orchestra in a state of complete anarchy, and although this was not an animation, I saw the possibility of writing a ludicrous '80s cartoon score using the new Fairlight.

So Lucas said, "Okay, write four songs for the film and if we like them you can do the score too." There is a band in the movie, four gorgeous nubile girls who deserve much better than the hole of a club in Cleveland, Ohio where they perform. The band is played by actresses and led by Lea Thompson who was excellent as Michael J. Fox's mother in Back to the Future. The director, Willard Huyck was keen that the girls themselves should sing the songs, and as it turned out they were actually excellent singers, though inexperienced. So in order to write songs within their limitations, and on account of their hectic shooting schedule, I decided to move to San Francisco for a while (where the movie was being shot), bringing in musicians I knew from the U.K. to play the instruments. I also called up Allee Willis, a very brilliant songwriter from Los Angeles to help me write the songs.

As it turned out, my presence on the set meant that the director and crew started to view me as a kind of resident rocker, and I started to get involved in everything from set design to choreography to suggesting camera angles. The toughest part though was teaching the girls to look and move like a rock band; we found that the only way was for them to plug in their instruments and learn to play for real. They worked incredibly hard to get it looking authentic, and in the process they got pretty good!

Lucas has the best sound and visual special effects facility in the world, and one of the interesting aspects of this was that I was able to incorporate sound effects into the score--for example, using the sound of trashbin lids as the bases for an alleyway sequence. Usually the music composer doesn't even meet the sound effects people until the final mix, and a lot of crucial cues end up being a tussle between the two. The best thing about it for me, though, was that I saw the making of a movie from start to finish, which convinced me that making my own films is what I could and should be doing.

EM: Some people are beginning to complain that the extensive use of instruments with the same factory presets, sampling instruments that use the same disks, and the wholesale sampling of other people's sounds is producing an objectionable similarity in current music. Do you feel this is a problem?

TD: I think it's like clothes, really. If you walk down a main street or around a shopping mall, most stores are selling the same ten or 12 items of clothing with different brand labels. You can kit yourself out in the latest fashions and be totally anonymous and boring and melt in with the crowd, or else you can use your ingenuity, go a little farther afield to second-hand shops and quirky designers, and set yourself apart, probably get noticed by much more interesting people. That's the way it is with music. You can work on the inside or on the outside, but the good stuff is usually well outside because it has that personality that sets it apart.

EM: How do you deal with the demands placed on the individual that "stardom" brings?

TD: I used to be very bad at knowing when to stop working. There was always something to be done that seemed totally worth doing, either for my career or for my artistic satisfaction. Or for my bank account! I don't believe pop stardom is very good for anyone as a human being. It requires that you put your vanity, your arrogance, your self-importance to the fore, and it leads you to believe that just because you have a special gift, you have to use it 24 hours a day, which is not true. I'm a lot better now at being a normal Joe Schmoe, unless I really need to be Thomas Dolby as the world regards him, like in front of a giant live TV audience. Not that I doubt the integrity of the rock legends like Springsteen who just are what they are, but personally I don't feel that I'm a piece of public domain, and I don't intend to live like one. Having said that, I do live for my work, and I am very, very grateful to have been successful at a job that I love. A lot of people aren't that lucky.

EM: When can we expect another Thomas Dolby solo album?

TD: I'm dying to get back to that, but also dreading it: specifically, the nightmare of playing the whole record company game in order to get the thing heard. What's nice about a movie is that there are no A&R people or radio programmers to decide what the public should or shouldn't hear.

EM: In what directions do you want to take your artistic impulses in the coming years?

TD: I think they'll decide that for themselves!

EM: Is your understanding of music mostly intuitive, or do you have a particular approach to making music?

TD: Everything I'm saying here is stuff that only crops up because you're asking me questions about it. Or else at dinner parties. I'm not an intellectual artist, I notice patterns and concepts in my work only in retrospect, as opposed to applying them in advance in a Brian Eno sort of way.

There is nothing wrong with that either, I mean I marvel constantly at the way he breaks the rules, but what I do is mainly intuitive and motivated by a puerile sense of mischief, and an incurable romance with this little planet and its occupants. There's no such thing as an "approach" or a "key" to art. Except maybe "approach with caution, it is armed and may be dangerous!"